Irish War of Independence and the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Irish War of Independence or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-military Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and its paramilitary forces the Auxiliaries and Ulster Special Constabulary (USC).

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of Independence. It provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State within a year as a self-governing dominion within the "community of nations known as the British Empire", a status "the same as that of the Dominion of Canada". It also provided Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which it exercised.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of Independence. It provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State within a year as a self-governing dominion within the "community of nations known as the British Empire", a status "the same as that of the Dominion of Canada". It also provided Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which it exercised.

The Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence occurred between 1919 – 1921. In December of 1921, the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty between the Irish and British governments concluded the Irish war for independence. The war resulted in over 2,000 deaths and the creation of the Irish Free State.

Before the Irish War of Independence

The nationalist population of Ireland had mostly turned against the British by the year 1918. This was inevitable due to the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising when the British resorted to punitive actions against known Irish Republicans.

Nationalists, of all hues, were horrified by the vengeful executions of the Republican leaders. Plus, with the British government’s cover-up of the murders of pacifist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, two pro-British journalists, T. Dickson, and Patrick MacIntyre, a youth and a republican activist Richard O’ Carroll. Murders committed by Capt. J. Bowen Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles.

Anti-British feelings were also exacerbated by the reports of atrocities committed by the South Staffordshire Regiment during the 1916 Uprising. In addition, these feelings were furthermore inflamed by the attempt to bring in conscription when the Germans began their Spring offensive during the World War I.

Nationalists, of all hues, were horrified by the vengeful executions of the Republican leaders. Plus, with the British government’s cover-up of the murders of pacifist Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, two pro-British journalists, T. Dickson, and Patrick MacIntyre, a youth and a republican activist Richard O’ Carroll. Murders committed by Capt. J. Bowen Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles.

Anti-British feelings were also exacerbated by the reports of atrocities committed by the South Staffordshire Regiment during the 1916 Uprising. In addition, these feelings were furthermore inflamed by the attempt to bring in conscription when the Germans began their Spring offensive during the World War I.

The general election of 1918

It was no wonder then, that in the November 1918 general election, the people of Ireland voted en masse for Sinn Féin, giving them 73 seats out of 105. Unionists won 22 seats, plus 3 for labor Unionists and 1 independent Unionist. 6 Nationalists won the remaining seats.

The victorious Sinn Féin party immediately refused to take part in the Westminster parliament. They did, however, set up the first Dáil Éireann that met for the first time on 21st January 1919 in the Mansion House, Dublin. This Dáil reaffirmed the 1916 Proclamation of Independence. They also reconstituted the Irish Volunteer Movement into the Irish Republican Army.

The start of the Irish War of Independence

On that very same day, the first act of war was committed. An IRA unit operating at Soloheadbeg in County Tipperary attacked and killed two RIC men escorting explosives. The unit was led by Seán Treacy and Dan Breen. Both men became famous guerilla fighters during the on-coming struggle.

As the year progressed there was an escalation of military action against the British administration and its mainly Catholic, armed police force, the RIC. Barracks were attacked throughout the country in a quest to obtain arms. RIC personnel was isolated from the community at large and a magistrate was killed in County Mayo.

There was, however, at the same time, a determined bid to build a state within a state. Sinn Féin set up an apparatus to wrest control of the country from the British by operating their own courts, etc.

Initially, the people were opposed to the violence whilst supporting the establishment of the new state. However, the reaction of the British was punitive, not to mention heavy-handed to the extreme.

Workers began to strike in Dublin, Limerick and elsewhere. Train drivers refused to carry British Army personnel and shops refused to serve RIC men. Unionist gunmen in Belfast launched anti-Catholic pogroms.

The IRA, led by Michael Collins, was to develop an excellent intelligence service, reaching into the very core of British Authority in Dublin Castle. By using his spies, Collins identified and eliminated the RIC detective murder squad known as the G-men. In retaliation, the British Army started to imprison people on suspicion and without trial.

Ireland was in a bad way by the late 1920s. IRA flying columns (bands of up to 100 men) were operating in many areas.

As the year progressed there was an escalation of military action against the British administration and its mainly Catholic, armed police force, the RIC. Barracks were attacked throughout the country in a quest to obtain arms. RIC personnel was isolated from the community at large and a magistrate was killed in County Mayo.

There was, however, at the same time, a determined bid to build a state within a state. Sinn Féin set up an apparatus to wrest control of the country from the British by operating their own courts, etc.

Initially, the people were opposed to the violence whilst supporting the establishment of the new state. However, the reaction of the British was punitive, not to mention heavy-handed to the extreme.

Workers began to strike in Dublin, Limerick and elsewhere. Train drivers refused to carry British Army personnel and shops refused to serve RIC men. Unionist gunmen in Belfast launched anti-Catholic pogroms.

The IRA, led by Michael Collins, was to develop an excellent intelligence service, reaching into the very core of British Authority in Dublin Castle. By using his spies, Collins identified and eliminated the RIC detective murder squad known as the G-men. In retaliation, the British Army started to imprison people on suspicion and without trial.

Ireland was in a bad way by the late 1920s. IRA flying columns (bands of up to 100 men) were operating in many areas.

The Black & Tans

Winston Churchill persuaded the British to establish a force of approximately 10,000 ex-army personnel to augment the RIC. This force, under the command of General Frank Crozier, was to become known as the Black and Tans.

The Black & Tans were brutal. Given a free-hand by the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, they went on to terrorise and murder many people. They burned homes, villages, towns, and even the centre of Cork city. Their viciousness tarnished Britain’s reputation all over the world.

The Black & Tans in Ireland achieved very little except to galvanise Irish resistance to Britain and, in reaction, IRA activity increased.

In November 1920, Collins issued orders to eliminate a British espionage unit of 14 men working in Dublin. British soldiers retaliated by opening fire at a football match in Croke Park stadium. They murdered 12 innocent civilians which became known as Bloody Sunday of 1920.

In December of 1920, the Government of Ireland Act was signed with the formation of Northern Ireland in 1921.

The Black & Tans were brutal. Given a free-hand by the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, they went on to terrorise and murder many people. They burned homes, villages, towns, and even the centre of Cork city. Their viciousness tarnished Britain’s reputation all over the world.

The Black & Tans in Ireland achieved very little except to galvanise Irish resistance to Britain and, in reaction, IRA activity increased.

In November 1920, Collins issued orders to eliminate a British espionage unit of 14 men working in Dublin. British soldiers retaliated by opening fire at a football match in Croke Park stadium. They murdered 12 innocent civilians which became known as Bloody Sunday of 1920.

In December of 1920, the Government of Ireland Act was signed with the formation of Northern Ireland in 1921.

The Blacks and Tans

A truce on the Irish War of Independence

By mid-1921, British morale was at its lowest. World opinion was against them, their powerful forces in Ireland could not defeat the IRA, a much smaller and poorly armed army of mostly part-time activists.

The IRA was also exhausted, they were short on arms and ammunition but had a very effective propaganda machine and so on 11th July 1921 both sides called a truce and both sides were to enter into negotiations that would result in the Anglo-Irish Treaty being signed.

It was then when Eamon DeValera, the president of Dáil Éireann, went to London to meet with the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George. They agreed an Irish delegation would go to London to discuss terms in the autumn.

The IRA was also exhausted, they were short on arms and ammunition but had a very effective propaganda machine and so on 11th July 1921 both sides called a truce and both sides were to enter into negotiations that would result in the Anglo-Irish Treaty being signed.

It was then when Eamon DeValera, the president of Dáil Éireann, went to London to meet with the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George. They agreed an Irish delegation would go to London to discuss terms in the autumn.

The Irish delegation

The delegation appointed by the Dáil to travel to London consisted of Arthur Griffith (Minister for Foreign Affairs and chairman of the delegation); Michael Collins (Minister for Finance and deputy chairman of the delegation); Robert Barton (Minister for Economic Affairs); George Gavan Duffy and Éamonn Duggan, with Erskine Childers, Fionán Lynch, Diarmuid O’Hegarty, and John Chartres providing secretarial assistance.

DeValera himself didn’t attend. Future historians wondered if he knew they wouldn’t be able to negotiate a 32 county Irish Republic.

DeValera himself didn’t attend. Future historians wondered if he knew they wouldn’t be able to negotiate a 32 county Irish Republic.

Éamon de Valera was a prominent statesman and political leader in 20th-century Ireland, serving several terms as head of government and head of state, with a prominent role introducing the Constitution of Ireland. Prior to de Valera's political career, he was a commandant at the 1916 Easter Rising. He was arrested, sentenced to death but released for a variety of reasons. He returned to Ireland and became one of the leading political figures of the War of Independence.

Michael Collins was an Irish revolutionary, soldier, and politician who was a leading figure in the early 20th-century Irish struggle for independence. He was Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State from January 1922 until his assassination in August 1922.

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, was a Welsh statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was the final Liberal to hold the post of prime minister, but his support increasingly came from the Conservatives who finally dropped him. To fund extensive welfare reforms he proposed taxes on land ownership and high incomes in the "People's Budget" (1909). At wartime, he strengthened the country's finances and forged agreements with trade unions to maintain production.

People to note:

The terms of the Treaty

During the debate, Lloyd George insisted that Ireland is to remain part of the Commonwealth and Dáil Éireann members to take the oath of allegiance to the British throne. After a delay of 2 months, Lloyd George delivered the ultimatum, sign a treaty within 3 days or there would be war.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was to give Ireland a 26 county Free State with Dominion status. The right to raise taxes, regulate foreign trade, independence in internal affairs, own an army, and the oath of allegiance was changed to one of fidelity.

The British were to retain 3 naval bases within the jurisdiction of the Free State, at Cobh, Lough Swilly, and at Berehaven. The Northern Ireland boundary would be determined by a commission. subsequently, this gave false hope to large tracts of Tyrone, Fermanagh Down, Armagh, and Derry City, which would be given to the Free State as they had Catholic majorities.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was to give Ireland a 26 county Free State with Dominion status. The right to raise taxes, regulate foreign trade, independence in internal affairs, own an army, and the oath of allegiance was changed to one of fidelity.

The British were to retain 3 naval bases within the jurisdiction of the Free State, at Cobh, Lough Swilly, and at Berehaven. The Northern Ireland boundary would be determined by a commission. subsequently, this gave false hope to large tracts of Tyrone, Fermanagh Down, Armagh, and Derry City, which would be given to the Free State as they had Catholic majorities.

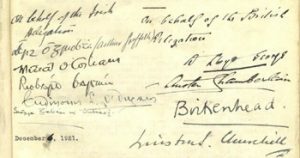

F. E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, the British Conservative politician, reportedly said on signing the treaty: "Mr Collins, in signing this Treaty I'm signing my political death warrant", to which Collins is said to have replied, "Lord Birkenhead, I'm signing my actual death warrant."

The signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Just after 2AM on the 6th December 1921, the Irish delegation, without consulting the Dáil, finally signed a treaty with the British.

The Treaty displeased the Catholics in the north and the unionists in the south. Meanwhile, many of those involved in the conflict were abhorred at the fact that not all of Ireland was to leave the United Kingdom.

The split over the treaty led to the Irish Civil War. In 1922, its two main Irish signatories, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, both died. F. E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, the British Conservative politician, reportedly said on signing the treaty: "Mr Collins, in signing this Treaty I'm signing my political death warrant", to which Collins is said to have replied, "Lord Birkenhead, I'm signing my actual death warrant." Collins was killed by anti-treaty republicans in an ambush at Béal na Bláth in August 1922, ten days after Griffith's death from heart failure which was ascribed to exhaustion. Both men were replaced in their posts by W. T. Cosgrave. Two of the other members of the delegation, Robert Barton and Erskine Childers, sided against the treaty in the civil war. Childers, head of anti-treaty propaganda in the conflict, was executed by the free state for possession of a pistol in November 1922.

The treaty's provisions relating to the monarch, the governor-general, and the treaty's own superiority in law were all deleted from the Constitution of the Irish Free State in 1932, following the enactment of the Statute of Westminster by the British Parliament. By this statute, the British Parliament had voluntarily relinquished its ability to legislate on behalf of dominions without their consent. Thus, the Government of the Irish Free State was free to change any laws previously passed by the British Parliament on their behalf.

Nearly 10 years earlier, Michael Collins had argued that the treaty would give "the freedom to achieve freedom". De Valera himself acknowledged the accuracy of this claim both in his actions in the 1930s but also in words he used to describe his opponents and their securing of independence during the 1920s. "They were magnificent", he told his son in 1932, just after he had entered government and read the files left by Cosgrave's Cumann na nGaedheal Executive Council.

The Treaty displeased the Catholics in the north and the unionists in the south. Meanwhile, many of those involved in the conflict were abhorred at the fact that not all of Ireland was to leave the United Kingdom.

The split over the treaty led to the Irish Civil War. In 1922, its two main Irish signatories, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, both died. F. E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead, the British Conservative politician, reportedly said on signing the treaty: "Mr Collins, in signing this Treaty I'm signing my political death warrant", to which Collins is said to have replied, "Lord Birkenhead, I'm signing my actual death warrant." Collins was killed by anti-treaty republicans in an ambush at Béal na Bláth in August 1922, ten days after Griffith's death from heart failure which was ascribed to exhaustion. Both men were replaced in their posts by W. T. Cosgrave. Two of the other members of the delegation, Robert Barton and Erskine Childers, sided against the treaty in the civil war. Childers, head of anti-treaty propaganda in the conflict, was executed by the free state for possession of a pistol in November 1922.

The treaty's provisions relating to the monarch, the governor-general, and the treaty's own superiority in law were all deleted from the Constitution of the Irish Free State in 1932, following the enactment of the Statute of Westminster by the British Parliament. By this statute, the British Parliament had voluntarily relinquished its ability to legislate on behalf of dominions without their consent. Thus, the Government of the Irish Free State was free to change any laws previously passed by the British Parliament on their behalf.

Nearly 10 years earlier, Michael Collins had argued that the treaty would give "the freedom to achieve freedom". De Valera himself acknowledged the accuracy of this claim both in his actions in the 1930s but also in words he used to describe his opponents and their securing of independence during the 1920s. "They were magnificent", he told his son in 1932, just after he had entered government and read the files left by Cosgrave's Cumann na nGaedheal Executive Council.

Exercises:

1. Re-read the text, make up a list of necessary vocabulary and answer the following questions:

1) Why did the Anti-British sentiments rise up so high in Ireland?

2) What party won the most seats during the general election of 1918 in Ireland?

3) What did the winners of the most seats do after the election?

4) How did the British government react to their actions?

5) How did the Irish War of Independence end?

6) What were the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty?

7) Did the Treaty please everyone in Ireland?

2. Find in the text the following words and word combinations, find a Russian equivalent for them and add them to your working vocabulary:

punitive actions; exacerbated; en masse; heavy-handed; to augment; to galvanise; oath of allegiance; abhorred; voluntarily relinquished.

3. Use the words from the Exercise 2 in your own sentences.

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.

1) Why did the Anti-British sentiments rise up so high in Ireland?

2) What party won the most seats during the general election of 1918 in Ireland?

3) What did the winners of the most seats do after the election?

4) How did the British government react to their actions?

5) How did the Irish War of Independence end?

6) What were the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty?

7) Did the Treaty please everyone in Ireland?

2. Find in the text the following words and word combinations, find a Russian equivalent for them and add them to your working vocabulary:

punitive actions; exacerbated; en masse; heavy-handed; to augment; to galvanise; oath of allegiance; abhorred; voluntarily relinquished.

3. Use the words from the Exercise 2 in your own sentences.

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.