Loss of India

From Bengal Famine of 1873–1874, through the Imperial Conference of 1926 and Indian Round Table Conferences of 1931-1933, to the Government of India Act of 1935 and the 'Quit India' movement of 1942, resulting in Indian Independence Act of 1947 and Indian partition into India and Pakistan.

The Bengal famine of 1873–1874

In addition, for the first time, inspection of villages by the government officials was carried out to identify those in need of aid or employment. In Sir Richard Temple's own description (in a contemporary correspondence), the generous aid allowed the labourers to stay in good physical condition and to return to their fields when the rains finally arrived; their actions put to rest any fears among relief officials that the government handouts were making the labourers "dependent."

Road construction became a major project of the famine relief works; the Road Cess Act of 1875, which was enacted just before the famine began, established a fund for the "construction of roads, especially their metaling and bridging." The construction of the Irrawaddy Valley State Railway in Burma, which began in 1874, also provided employment in the earthworks for many famine immigrants from Bengal.

Road construction became a major project of the famine relief works; the Road Cess Act of 1875, which was enacted just before the famine began, established a fund for the "construction of roads, especially their metaling and bridging." The construction of the Irrawaddy Valley State Railway in Burma, which began in 1874, also provided employment in the earthworks for many famine immigrants from Bengal.

The Bihar famine of 1873–1874 (and the Bengal famine of 1873–1874) was a famine in British India that followed a drought in the province of Bihar, the neighbouring provinces of Bengal, the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. It affected an area of 140,000 square kilometres and a population of 21.5 million. The relief effort—organised by Sir Richard Temple, the newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal—was one of the success stories of the famine relief in British India; there was little or no mortality during the famine.

As the impending famine came to light, a decision was made at the highest level to save lives at any cost. 40 million Indian rupees were spent on importing 450,000 tons of rice from Burma. Another 22.5 million Indian rupees were spent in organising relief for 300 million units (1 unit = one person for one day).

As the impending famine came to light, a decision was made at the highest level to save lives at any cost. 40 million Indian rupees were spent on importing 450,000 tons of rice from Burma. Another 22.5 million Indian rupees were spent in organising relief for 300 million units (1 unit = one person for one day).

Starving Indian family during the subsequent, Great, famine

The Aftermath

The famine proved to be less severe than had originally been anticipated, and 100,000 tons of grain was left unused at the end of the relief effort. According to some, the total government expense was 50 percent more than the total budget of a similar relief effort during the Maharashtra famine of 1973 (in independent India), after adjusting for inflation.

Since the expenditure associated with the relief effort was considered excessive, Sir Richard Temple was criticised by British officials. Taking the criticism to heart, he revised the official famine relief philosophy, which thereafter became concerned with thrift and efficiency. The relief efforts in the subsequent Great Famine of 1876–78 in Bombay and South India were therefore very modest, which led to excessive mortality that has been estimated to lie in a range whose low end is approximately 5.5 million human deaths, the high end approximately is 9.6 million deaths and a careful modern demographic estimate of which is 8.2 million deaths.

The Great Famine, in turn, had a much bigger and more lasting political impact on events in India. Among the British administrators in India who were unsettled by the official reactions to the famine and, in particular by the stifling of the official debate about the best form of famine relief, were William Wedderburn and A. O. Hume. Less than a decade later, they would found the Indian National Congress and, in turn, influence a generation of Indian nationalists. Among the latter were Dadabhai Naoroji and Romesh Chunder Dutt for whom the Great Famine would become a cornerstone of the economic critique of the British Raj.

Since the expenditure associated with the relief effort was considered excessive, Sir Richard Temple was criticised by British officials. Taking the criticism to heart, he revised the official famine relief philosophy, which thereafter became concerned with thrift and efficiency. The relief efforts in the subsequent Great Famine of 1876–78 in Bombay and South India were therefore very modest, which led to excessive mortality that has been estimated to lie in a range whose low end is approximately 5.5 million human deaths, the high end approximately is 9.6 million deaths and a careful modern demographic estimate of which is 8.2 million deaths.

The Great Famine, in turn, had a much bigger and more lasting political impact on events in India. Among the British administrators in India who were unsettled by the official reactions to the famine and, in particular by the stifling of the official debate about the best form of famine relief, were William Wedderburn and A. O. Hume. Less than a decade later, they would found the Indian National Congress and, in turn, influence a generation of Indian nationalists. Among the latter were Dadabhai Naoroji and Romesh Chunder Dutt for whom the Great Famine would become a cornerstone of the economic critique of the British Raj.

Churchill at the Imperial Conference, October 1926 (LAC)

Imperial Conference of 1926

The 1926 Imperial Conference was the seventh Imperial Conference bringing together the prime ministers of the Dominions of the British Empire. It was held in London from 19 October to 22 November 1926. The conference was notable for producing the Balfour Declaration, which established the principle that the dominions are all equal in status, and "autonomous communities within the British Empire" not subordinate to the United Kingdom. The term "Commonwealth" was officially adopted to describe the community.

The conference was arranged to follow directly after the 1926 Assembly of the League of Nations (in Geneva, Switzerland), to reduce the amount of travelling required for the dominions' representatives.

The conference created the Inter-Imperial Relations Committee, chaired by Arthur Balfour, to look into future constitutional arrangements for the Commonwealth. In the end, the committee rejected the idea of a codified constitution, as espoused by South Africa's former Prime Minister Jan Smuts, but also fell short of endorsing the "end of empire" espoused by Smuts's arch-rival, Barry Hertzog. The recommendations were adopted unanimously by the conference on 15 November, followed by an equally warm reception in the newspapers.

Essentially, the conference finally defined the constitutional status of the Dominions, acknowledging their right to full internal self-government and leaving it up to them as to whether they went along with British foreign policy. This marked the end of any hope that the empire might retain a fully coherent and binding set of external policies. Indeed, it would be left to the Dominions to decide whether they wished to take Britain’s side in any future war.

The conference was arranged to follow directly after the 1926 Assembly of the League of Nations (in Geneva, Switzerland), to reduce the amount of travelling required for the dominions' representatives.

The conference created the Inter-Imperial Relations Committee, chaired by Arthur Balfour, to look into future constitutional arrangements for the Commonwealth. In the end, the committee rejected the idea of a codified constitution, as espoused by South Africa's former Prime Minister Jan Smuts, but also fell short of endorsing the "end of empire" espoused by Smuts's arch-rival, Barry Hertzog. The recommendations were adopted unanimously by the conference on 15 November, followed by an equally warm reception in the newspapers.

Essentially, the conference finally defined the constitutional status of the Dominions, acknowledging their right to full internal self-government and leaving it up to them as to whether they went along with British foreign policy. This marked the end of any hope that the empire might retain a fully coherent and binding set of external policies. Indeed, it would be left to the Dominions to decide whether they wished to take Britain’s side in any future war.

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905.

As Foreign Secretary in the Lloyd George ministry, he issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917 on behalf of the cabinet.

As Foreign Secretary in the Lloyd George ministry, he issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917 on behalf of the cabinet.

General James Barry Munnik Hertzog KC, better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog, was a South African politician and soldier.

He was a Boer general during the Second Boer War who became Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1924 to 1939. Throughout his life he encouraged the development of Afrikaner culture, determined to prevent Afrikaners from being influenced by British culture. He is the only South African Prime Minister to have served under three British monarchs: George V, Edward VIII, and George VI.

He was a Boer general during the Second Boer War who became Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1924 to 1939. Throughout his life he encouraged the development of Afrikaner culture, determined to prevent Afrikaners from being influenced by British culture. He is the only South African Prime Minister to have served under three British monarchs: George V, Edward VIII, and George VI.

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts was a South African statesman, military leader, and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 to 1924 and 1939 to 1948.

People to note:

Indian Round Table Conferences of 1931-1933

The three Round Table Conferences of 1930–1932 were a series of peace conferences organised by the British Government and Indian political personalities to discuss constitutional reforms in India. These started in November 1930 and ended in December 1932. They were conducted as per the recommendation of Jinnah to Viceroy Lord Irwin and Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, and by the report submitted by the Simon Commission in May 1930. Demands for Swaraj, or self-rule, in India had been growing increasingly strong. B. R. Ambedkar, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, V. S. Srinivasa Sastri, Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, K. T. Paul and Mirabehn are key participants from India. By the 1930s, many British politicians believed that India needed to move towards dominion status. However, there were significant disagreements between the Indian and the British political parties that the Conferences would not resolve. The key topic was about constitution and India which was mainly discussed in that conference. There were three Round Table Conferences from 1930 to 1932.

On the occasion of the All India Muslim League session, 1936

Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935.

The most significant aspects of the Act were:

· ㅤthe grant of a large measure of autonomy to the provinces of British India (ending the system of diarchy introduced by the Government of India Act 1919)

· ㅤprovision for the establishment of a "Federation of India", to be made up of both British India and some or all of the "princely states"

· ㅤthe introduction of direct elections, thus increasing the franchise from seven million to thirty-five million people

· ㅤa partial reorganisation of the provinces:

· ㅤSindh was separated from Bombay

· ㅤBihar and Orissa was split into separate provinces of Bihar and Orissa

· ㅤBurma was completely separated from India

· ㅤAden was also detached from India, and established as a separate Crown colony

· ㅤmembership of the provincial assemblies was altered so as to include any number of elected Indian representatives, who were now able to form majorities and be appointed to form governments

· ㅤthe establishment of a Federal Court

However, the degree of autonomy introduced at the provincial level was subject to important limitations: the provincial Governors retained important reserve powers, and the British authorities also retained a right to suspend responsible government.

The parts of the Act intended to establish the Federation of India never came into operation, due to opposition from rulers of the princely states. The remaining parts of the Act came into force in 1937, when the first elections under the Act were also held. This Act provided for the establishment of all India federation consisting of provinces and princely states as units. The act divided the powers between centre and units in terms of three lists: Federal list, Provincial list and the con current list.

The reception of the Act was mostly negative. Nehru, the Indian independence activist and then Prime Minister of India, called it "a machine with strong brakes but no engine". He also called it a "Charter of Slavery". Jinnah, the Muslim politician and founder of Pakistan, called it, "thoroughly rotten, fundamentally bad and totally unacceptable."

Winston Churchill conducted a campaign against Indian self-government from 1929 onwards. When the bill passed, he denounced it in the House of Commons as "a gigantic quilt of jumbled crochet work, a monstrous monument of shame built by pygmies". Leo Amery, who spoke next, opened his speech with the words "Here endeth the last chapter of the Book of Jeremiah" and commented that Churchill's speech had been "not only a speech without a ray of hope; it was a speech from beginning to end, like all his speeches on the subject, utterly and entirely negative and devoid of constructive thought."

Rab Butler, who as Under-Secretary for India helped pilot the Act through the House of Commons, later wrote that it helped to set India on the path of Parliamentary democracy. Butler blamed Jinnah for the subsequent secession of Pakistan, likening his strength of character to that of the Ulster Unionist leader Edward Carson, and wrote that "men like Jinnah are not born every day", although he also blamed Congress for not having done enough to court the Muslims. In 1954 Butler stayed in Delhi, where Nehru, who Butler believed had mellowed somewhat from his extreme views of the 1930s, told him that the Act, based on the English constitutional principles of Dicey and Anson, had been the foundation of the Indian Independence Bill.

The most significant aspects of the Act were:

· ㅤthe grant of a large measure of autonomy to the provinces of British India (ending the system of diarchy introduced by the Government of India Act 1919)

· ㅤprovision for the establishment of a "Federation of India", to be made up of both British India and some or all of the "princely states"

· ㅤthe introduction of direct elections, thus increasing the franchise from seven million to thirty-five million people

· ㅤa partial reorganisation of the provinces:

· ㅤSindh was separated from Bombay

· ㅤBihar and Orissa was split into separate provinces of Bihar and Orissa

· ㅤBurma was completely separated from India

· ㅤAden was also detached from India, and established as a separate Crown colony

· ㅤmembership of the provincial assemblies was altered so as to include any number of elected Indian representatives, who were now able to form majorities and be appointed to form governments

· ㅤthe establishment of a Federal Court

However, the degree of autonomy introduced at the provincial level was subject to important limitations: the provincial Governors retained important reserve powers, and the British authorities also retained a right to suspend responsible government.

The parts of the Act intended to establish the Federation of India never came into operation, due to opposition from rulers of the princely states. The remaining parts of the Act came into force in 1937, when the first elections under the Act were also held. This Act provided for the establishment of all India federation consisting of provinces and princely states as units. The act divided the powers between centre and units in terms of three lists: Federal list, Provincial list and the con current list.

The reception of the Act was mostly negative. Nehru, the Indian independence activist and then Prime Minister of India, called it "a machine with strong brakes but no engine". He also called it a "Charter of Slavery". Jinnah, the Muslim politician and founder of Pakistan, called it, "thoroughly rotten, fundamentally bad and totally unacceptable."

Winston Churchill conducted a campaign against Indian self-government from 1929 onwards. When the bill passed, he denounced it in the House of Commons as "a gigantic quilt of jumbled crochet work, a monstrous monument of shame built by pygmies". Leo Amery, who spoke next, opened his speech with the words "Here endeth the last chapter of the Book of Jeremiah" and commented that Churchill's speech had been "not only a speech without a ray of hope; it was a speech from beginning to end, like all his speeches on the subject, utterly and entirely negative and devoid of constructive thought."

Rab Butler, who as Under-Secretary for India helped pilot the Act through the House of Commons, later wrote that it helped to set India on the path of Parliamentary democracy. Butler blamed Jinnah for the subsequent secession of Pakistan, likening his strength of character to that of the Ulster Unionist leader Edward Carson, and wrote that "men like Jinnah are not born every day", although he also blamed Congress for not having done enough to court the Muslims. In 1954 Butler stayed in Delhi, where Nehru, who Butler believed had mellowed somewhat from his extreme views of the 1930s, told him that the Act, based on the English constitutional principles of Dicey and Anson, had been the foundation of the Indian Independence Bill.

"Quit India", the movement led by Mahatma Gandhi

On August 8, year 1942, Mahatma Gandhi gave the call for British colonisers to “Quit India” and for the Indians to “do or die” to make this happen. Soon after, Gandhi and almost the entire top Congress leadership was arrested, and thus began a truly people-led movement in our freedom struggle, eventually quelled violently by the British, but leaving behind a clear message – the British would have to leave India, and no other solution would be acceptable to its masses.

“Here is a mantra, a short one, that I give you. Imprint it on your hearts, so that in every breath you give expression to it. The mantra is: ‘Do or Die’. We shall either free India or die trying; we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery.”

— Mahatma Gandhi

— Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist, who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule, and in turn inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (Sanskrit: "great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, is now used throughout the world.

What led to the events of August 1942

While factors leading to such a movement had been building up, matters came to a head with the failure of the Cripps Mission.

The World War II was raging, and a beleaguered British needed the cooperation of their colonial subjects in India. To this end, in March 1942, a mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps arrived in India to meet leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League. The idea was to secure India’s whole-hearted support in the war, in return for self-governance.

However, despite the promise of “the earliest possible realisation of self-government in India”, the offer Cripps made was of dominion status, and not freedom. Also, there was a provision of the partition of India, which was not acceptable to the Congress.

The failure of the Cripps Mission made Mahatma Gandhi realise that freedom would be had only by fighting tooth and nail for it. Though initially reluctant to launch a movement that could hamper Britain’s efforts to defeat Fascist forces in the World War, the Congress eventually decided to launch a mass civil disobedience. At the Working Committee meeting in Wardha in July 1942, it was decided the time had come for the movement to move into an active phase.

The World War II was raging, and a beleaguered British needed the cooperation of their colonial subjects in India. To this end, in March 1942, a mission led by Sir Stafford Cripps arrived in India to meet leaders of the Congress and the Muslim League. The idea was to secure India’s whole-hearted support in the war, in return for self-governance.

However, despite the promise of “the earliest possible realisation of self-government in India”, the offer Cripps made was of dominion status, and not freedom. Also, there was a provision of the partition of India, which was not acceptable to the Congress.

The failure of the Cripps Mission made Mahatma Gandhi realise that freedom would be had only by fighting tooth and nail for it. Though initially reluctant to launch a movement that could hamper Britain’s efforts to defeat Fascist forces in the World War, the Congress eventually decided to launch a mass civil disobedience. At the Working Committee meeting in Wardha in July 1942, it was decided the time had come for the movement to move into an active phase.

The Gowalia Tank address by Gandhi

On August 8, Bapu addressed the people from Mumbai’s Gowalia Tank maidan. “Here is a mantra, a short one, that I give you. Imprint it on your hearts, so that in every breath you give expression to it. The mantra is: ‘Do or Die’. We shall either free India or die trying; we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery,” Gandhi said. Aruna Asaf Ali hoisted the Tricolour on the ground, and the Quit India movement had been officially announced.

By August 9, Gandhi and all other senior Congress leaders had been jailed. Bapu was kept at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune, and later in the Yerawada jail. It was during this time that Kasturba Gandhi died at the Aga Khan Palace.

By August 9, Gandhi and all other senior Congress leaders had been jailed. Bapu was kept at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune, and later in the Yerawada jail. It was during this time that Kasturba Gandhi died at the Aga Khan Palace.

People’s movement

The arrest of the leaders, however, failed to deter the masses. With no one to give directions, people took the movement into their own hands.

In Bombay, Poona and Ahmedabad, lakhs of people clashed with the police on August 9. On August 10, protests erupted in Delhi, UP and Bihar. There were strikes, demonstrations and people’s marches in defiance of prohibitory orders in Kanpur, Patna, Varanasi, and Allahabad.

The protests spread rapidly into smaller towns and villages. Till mid-September, police stations, courts, post offices and other symbols of government authority were attacked. Railway tracks were blocked, students went on strike in schools and colleges across India, and distributed illegal nationalist literature. Mill and factory workers in Bombay, Ahmedabad, Poona, Ahmednagar, and Jamshedpur stayed away for weeks.

In some places, the protests were violent, with bridges blown up, telegraph wires cut, and railway lines taken apart.

Ram Manohar Lohia, describing the movement on its 25th anniversary, wrote: “9th August was and will remain a people’s event. 15th August was a state event… 9th August 1942 expressed the will of the people — we want to be free, and we shall be free. For the first time after a long period in our history, crores of people expressed their desire to be free…”

In Bombay, Poona and Ahmedabad, lakhs of people clashed with the police on August 9. On August 10, protests erupted in Delhi, UP and Bihar. There were strikes, demonstrations and people’s marches in defiance of prohibitory orders in Kanpur, Patna, Varanasi, and Allahabad.

The protests spread rapidly into smaller towns and villages. Till mid-September, police stations, courts, post offices and other symbols of government authority were attacked. Railway tracks were blocked, students went on strike in schools and colleges across India, and distributed illegal nationalist literature. Mill and factory workers in Bombay, Ahmedabad, Poona, Ahmednagar, and Jamshedpur stayed away for weeks.

In some places, the protests were violent, with bridges blown up, telegraph wires cut, and railway lines taken apart.

Ram Manohar Lohia, describing the movement on its 25th anniversary, wrote: “9th August was and will remain a people’s event. 15th August was a state event… 9th August 1942 expressed the will of the people — we want to be free, and we shall be free. For the first time after a long period in our history, crores of people expressed their desire to be free…”

Outcome

The Quit India movement was violently suppressed by the British – people were shot, lathi charged, villages burnt and enormous fines imposed. In the five months up to December 1942, an estimated 60,000 people had been thrown in jail.

However, though the movement was quelled, it changed the character of the Indian freedom struggle, with the masses rising up to articulate as they had never before – the British masters would have to Quit India.

However, though the movement was quelled, it changed the character of the Indian freedom struggle, with the masses rising up to articulate as they had never before – the British masters would have to Quit India.

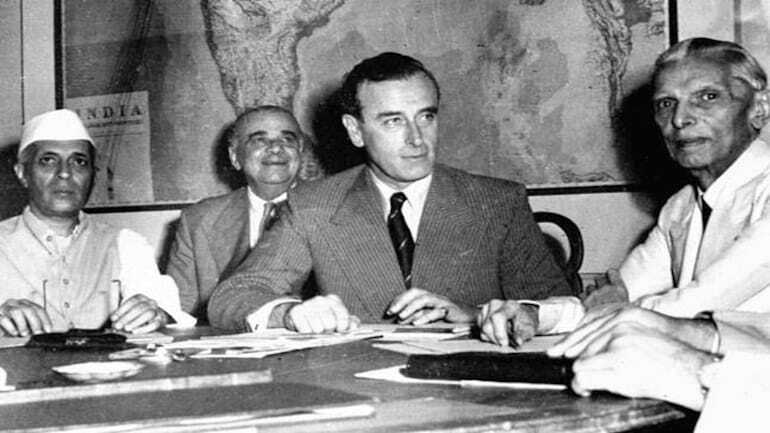

Indian Independence Act of 1947

Britain’s Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act in July 1947.

The Act's most important provisions were:

·ㅤdivision of British India into the two new dominions of India and Pakistan, with effect from 15 August 1947.

·ㅤpartition of the provinces of Bengal and Punjab between the two new countries.

·ㅤestablishment of the office of Governor-General in each of the two new countries, as representatives of the Crown.

·ㅤconferral of complete legislative authority upon the respective Constituent Assemblies of the two new countries.

·ㅤtermination of British suzerainty over the princely states, with effect from 15 August 1947.These states could decide to join either India or Pakistan.

·ㅤAbolition of the use of the title "Emperor of India" by the British monarch (this was subsequently executed by King George VI by royal proclamation on 22 June 1948).

The Act's most important provisions were:

·ㅤdivision of British India into the two new dominions of India and Pakistan, with effect from 15 August 1947.

·ㅤpartition of the provinces of Bengal and Punjab between the two new countries.

·ㅤestablishment of the office of Governor-General in each of the two new countries, as representatives of the Crown.

·ㅤconferral of complete legislative authority upon the respective Constituent Assemblies of the two new countries.

·ㅤtermination of British suzerainty over the princely states, with effect from 15 August 1947.These states could decide to join either India or Pakistan.

·ㅤAbolition of the use of the title "Emperor of India" by the British monarch (this was subsequently executed by King George VI by royal proclamation on 22 June 1948).

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly formed states in the months immediately following the partition. There was no conception that population transfers would be necessary because of the partitioning. Religious minorities were expected to stay put in the states they found themselves residing in. However, an exception was made for Punjab, where the transfer of populations was organised because of the communal violence affecting the province. This did not apply to other provinces.

Racing the deadline, two boundary commissions worked desperately to partition Punjab and Bengal in such a way as to leave the maximum practical number of Muslims to the west of the former’s new boundary and to the east of the latter’s, but, as soon as the new borders were known, roughly 15 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs fled from their homes on one side of the newly demarcated borders to what they thought would be “shelter” on the other. In the course of that tragic exodus of innocents, as many as a million people were slaughtered in communal massacres that made all previous conflicts of the sort known to recent history pale by comparison. Sikhs, settled astride Punjab’s new “line,” suffered the highest proportion of casualties relative to their numbers.

Racing the deadline, two boundary commissions worked desperately to partition Punjab and Bengal in such a way as to leave the maximum practical number of Muslims to the west of the former’s new boundary and to the east of the latter’s, but, as soon as the new borders were known, roughly 15 million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs fled from their homes on one side of the newly demarcated borders to what they thought would be “shelter” on the other. In the course of that tragic exodus of innocents, as many as a million people were slaughtered in communal massacres that made all previous conflicts of the sort known to recent history pale by comparison. Sikhs, settled astride Punjab’s new “line,” suffered the highest proportion of casualties relative to their numbers.

Exercises:

1. Find in the text the following words and realia, find a Russian equivalent for them if possible, and add them to your working vocabulary:

thrift; come to light; famine relief; expenditure; cornerstone; Commonwealth, unanimously; Swaraj;royal assent; secession; lathi charge; to quell; to erupt.

2. Watch the video above, listen to it and tell us what was said there.

3. Re-read the text and answer the following questions:

1) What led to the Bengal Famine?

2) How did the British government direct the relief effort?

3) How did the famine end, and what did it subsequently lead to?

4) What was the subject of discussion of the Imperial Conference of 1926?

5) What was the belief of many British politicians after Indian Round Table Conferences of 1931-1933?

6) How did the Indian populace react to the Government of India Act 1935?

7) Who was Mahatma Gandhi and what is he known for?

8) What provoked the creation of the "Quit India" movement?

9) What was the British Empire's reaction to it?

10) How did the "Quit India" movement end?

11) What was the Indian Independence Act of 1947 about?

4. Match the realia and events by the cause-effect link:

1) The Bengal famine; 2) The Commonwealth; 3) ‘Do or Die’ ; 4) ‘Quit India’ ; 5) Indian Independence Act of 1947; 6) Government of India Act 1935

a) Indian constitution reform; b) Expenditure considered excessive; c) People’s movement; d) Seccession of India; e) The call of Gandhi; f) Countries within the British Empire

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.

5. Look up information on the Internet and prepare to write an essay on the topic:

"A Jewel in the Crown: What does India mean to the British colonial empire?"

6. Split into groups according to points of view and prepare your arguments to debate with your groupmates on the following question:

"Is it worse to overspend on famine relief effort and risk not having enough money and resources to save people from an even more devastating one around the corner, or not spend enough and risk your citizens and their approval here and now?"

thrift; come to light; famine relief; expenditure; cornerstone; Commonwealth, unanimously; Swaraj;royal assent; secession; lathi charge; to quell; to erupt.

2. Watch the video above, listen to it and tell us what was said there.

3. Re-read the text and answer the following questions:

1) What led to the Bengal Famine?

2) How did the British government direct the relief effort?

3) How did the famine end, and what did it subsequently lead to?

4) What was the subject of discussion of the Imperial Conference of 1926?

5) What was the belief of many British politicians after Indian Round Table Conferences of 1931-1933?

6) How did the Indian populace react to the Government of India Act 1935?

7) Who was Mahatma Gandhi and what is he known for?

8) What provoked the creation of the "Quit India" movement?

9) What was the British Empire's reaction to it?

10) How did the "Quit India" movement end?

11) What was the Indian Independence Act of 1947 about?

4. Match the realia and events by the cause-effect link:

1) The Bengal famine; 2) The Commonwealth; 3) ‘Do or Die’ ; 4) ‘Quit India’ ; 5) Indian Independence Act of 1947; 6) Government of India Act 1935

a) Indian constitution reform; b) Expenditure considered excessive; c) People’s movement; d) Seccession of India; e) The call of Gandhi; f) Countries within the British Empire

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.

5. Look up information on the Internet and prepare to write an essay on the topic:

"A Jewel in the Crown: What does India mean to the British colonial empire?"

6. Split into groups according to points of view and prepare your arguments to debate with your groupmates on the following question:

"Is it worse to overspend on famine relief effort and risk not having enough money and resources to save people from an even more devastating one around the corner, or not spend enough and risk your citizens and their approval here and now?"