The rise of Germany

The rise of Germany in the 19th century was a sequence of events from the unification of the German states under the leadership of Prussia by Otto von Bismarck, followed by establishing Germany as a colonial power after establishing 'Weltpolitik' in favour of the old "Realpolitik", adopting a more aggressive approach to diplomacy, which subsequently somewhat harmed British own colonial standing and status as a naval superpower.

What is Realpolitik?

Realpolitik (from German: real; "realistic", "practical", or "actual"; and Politik; "politics") is politics or diplomacy based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical premises, focused around settling on the second best while still striving for the most preferred solution, instead of stubbornly chasing the only "acceptable" option. In this respect, it shares aspects of its philosophical approach with those of realism and pragmatism. It is often simply referred to as "pragmatism" in politics, e.g. "pursuing pragmatic policies".

The Unification of Germany

The main issue that confronted the idea of German unification by the mid-nineteenth century was the idea of a “greater” Germany versus a “smaller” Germany. The concept of a “smaller” Germany was that a unified German entity should exclude Austria, while the idea of “greater" Germany was that Germany should include the Kingdom of Austria. Proponents of “smaller” Germany argued that Austria’s inclusion would only cause difficulties for German policy, as the Kingdom of Austria was part of the greater Austrian Empire, which included large swaths of land in Central and Southeastern Europe that was composed of nearly 15 different minorities. Those who favoured “greater” Germany pointed to the traditional role played by Austria, which was mostly composed of Germans, and the Habsburg rulers in German affairs.

The first successful attempt at German unification was undertaken by Otto von Bismarck, the Prime Minister of Prussia. Bismarck was a proponent of “smaller” Germany, not to mention a master at the game of realpolitik. German unification was achieved by the force of Prussia, and enforced from the top-down, meaning that it was not an organic movement that was fully supported and spread by the popular classes but instead was a product of Prussian royal policies.

The first successful attempt at German unification was undertaken by Otto von Bismarck, the Prime Minister of Prussia. Bismarck was a proponent of “smaller” Germany, not to mention a master at the game of realpolitik. German unification was achieved by the force of Prussia, and enforced from the top-down, meaning that it was not an organic movement that was fully supported and spread by the popular classes but instead was a product of Prussian royal policies.

The first war of German unification was the 1862 Danish War, begun over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Bismarck allied with Austria to fight the Danes in a war to protect the interests of Holstein, a member of the German Confederation.

The second war of German unification was the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, which settled the question of “smaller” versus “greater” Germany. This brief war (fought over the course of mere weeks) pitted Prussia and her allies against Austria and other German states. Prussia won and directly annexed some of the German states that had sided with Austria (such as Hanover and Nassau). In an act of leniency, Prussia allowed some of the larger Austrian allies to maintain their independence, such as Baden and Bavaria. In 1867 Bismarck created the North German Confederation, a union of the northern German states under the hegemony of Prussia. Several other German states joined, and the North German Confederation served as a model for the future German Empire.

The third and final act of German unification was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, orchestrated by Bismarck to draw the western German states into alliance with the North German Confederation. With the French defeat, the German Empire was proclaimed in January 1871 in the Palace at Versailles, France. From this point forward, foreign policy of the German Empire was made in Berlin, with the German Kaiser (who was also the King of Prussia) accrediting ambassadors of foreign nations.

The second war of German unification was the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, which settled the question of “smaller” versus “greater” Germany. This brief war (fought over the course of mere weeks) pitted Prussia and her allies against Austria and other German states. Prussia won and directly annexed some of the German states that had sided with Austria (such as Hanover and Nassau). In an act of leniency, Prussia allowed some of the larger Austrian allies to maintain their independence, such as Baden and Bavaria. In 1867 Bismarck created the North German Confederation, a union of the northern German states under the hegemony of Prussia. Several other German states joined, and the North German Confederation served as a model for the future German Empire.

The third and final act of German unification was the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, orchestrated by Bismarck to draw the western German states into alliance with the North German Confederation. With the French defeat, the German Empire was proclaimed in January 1871 in the Palace at Versailles, France. From this point forward, foreign policy of the German Empire was made in Berlin, with the German Kaiser (who was also the King of Prussia) accrediting ambassadors of foreign nations.

Bismarck's ambivalence towards colonialism

Until their 1871 unification, the German states had not concentrated on the development of a navy, and this essentially had precluded German participation in earlier imperialist scrambles for remote colonial territory—the so-called “place in the sun.” Germany seemed destined to play catch-up. The German states prior to 1870 retained separate political structures and goals, and German foreign policy up to and including the age of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck concentrated on resolving the “German question” in Europe and securing German interests on the continent.

Many Germans in the late 19th century viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of nationhood. Public opinion eventually arrived at an understanding that prestigious African and Pacific colonies went hand-in-hand with dreams of a world-class navy. Both aspirations would become reality, nurtured by a press replete with Kolonialfreunde (supporters of colonial acquisitions) and a myriad of geographical associations and colonial societies. Bismarck and many deputies in the Reichstag had no interest in colonial conquests merely to acquire square miles of territory.

In essence, Bismarck’s colonial motives were obscure as he had said repeatedly “…I am no man for colonies.” However, in 1884 he consented to the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire to protect trade, safeguard raw materials and export markets, and take opportunities for capital investment, among other reasons. In the very next year Bismarck shed personal involvement when he, according to Edward Crankshaw, “abandoned his colonial drive as suddenly and casually as he had started it” as if he had committed an error in judgement that could confuse the substance of his more significant policies. Bismarck even tried to give German South-West Africa away to the British.

Many Germans in the late 19th century viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of nationhood. Public opinion eventually arrived at an understanding that prestigious African and Pacific colonies went hand-in-hand with dreams of a world-class navy. Both aspirations would become reality, nurtured by a press replete with Kolonialfreunde (supporters of colonial acquisitions) and a myriad of geographical associations and colonial societies. Bismarck and many deputies in the Reichstag had no interest in colonial conquests merely to acquire square miles of territory.

In essence, Bismarck’s colonial motives were obscure as he had said repeatedly “…I am no man for colonies.” However, in 1884 he consented to the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire to protect trade, safeguard raw materials and export markets, and take opportunities for capital investment, among other reasons. In the very next year Bismarck shed personal involvement when he, according to Edward Crankshaw, “abandoned his colonial drive as suddenly and casually as he had started it” as if he had committed an error in judgement that could confuse the substance of his more significant policies. Bismarck even tried to give German South-West Africa away to the British.

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg (1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), known as Otto von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman who masterminded the unification of Germany in 1871 and served as its first chancellor until 1890, in which capacity he dominated European affairs for two decades.

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 1859 – 4 June 1941), was the last German Emperor (Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening Germany's position as a great power, his tactless public statements greatly antagonised the international community and his foreign policy was seen by many as one of the causes for the outbreak of World War I.

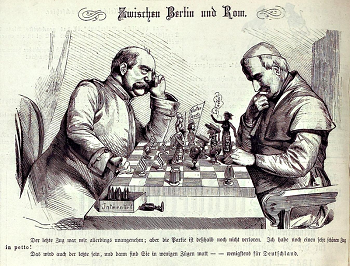

Otto Von Bismarck’s Ambivalence: Cartoon from 1884.

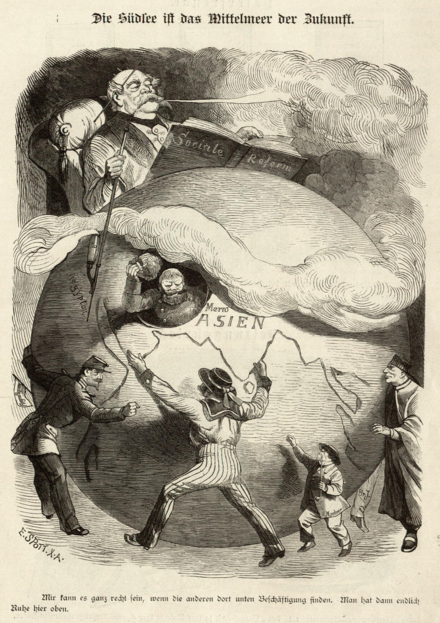

Bismarck is happy with other nations being busy “down there.”

Bismarck is happy with other nations being busy “down there.”

In 1891, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany made a decisive break with former “Realpolitik” of Bismarck and established “Weltpolitik” (“world policy”). The aim of Weltpolitik was to transform Germany into a global power through aggressive diplomacy, the acquisition of overseas colonies, and the development of a large navy.

The origins of the policy can be traced to a Reichstag debate in December 1897 during which German Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bülow stated, “in one word: We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we demand our own place in the sun.”

The origins of the policy can be traced to a Reichstag debate in December 1897 during which German Foreign Secretary Bernhard von Bülow stated, “in one word: We wish to throw no one into the shade, but we demand our own place in the sun.”

Acquisition of Colonies

The rise of German imperialism and colonialism coincided with the latter stages of the “Scramble for Africa” during which enterprising German individuals, rather than government entities, competed with other already established colonies and colonialist entrepreneurs. With the Germans joining the race for the last uncharted territories in Africa and the Pacific that had not yet been carved up, competition for colonies involved major European nations and several lesser powers.

The German effort included the first commercial enterprises in the 1850s and 1860s in West Africa, East Africa, the Samoan Islands, and the unexplored north-east quarter of New Guinea with adjacent islands. German traders and merchants began to establish themselves in the African Cameroon delta and the mainland coast across from Zanzibar. At Apia and the settlements Finschhafen, Simpsonhafen and the islands Neu-Pommern and Neu-Mecklenburg, trading companies newly fortified with credit began expansion into coastal landholding. Large African inland acquisitions followed, mostly to the detriment of native inhabitants. All in all, German colonies comprised territory that makes up 22 countries today, mostly in Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, and Uganda.

As Bismarck was converted to the colonial idea by 1884, he favoured “chartered company” land management rather than establishment of colonial government due to financial considerations. Although temperate zone cultivation flourished, the demise and often failure of tropical low-land enterprises contributed to changing Bismarck’s view. He reluctantly acquiesced to pleas for help to deal with revolts and armed hostilities by often powerful rulers whose lucrative slaving activities seemed at risk. German native military forces initially engaged in dozens of punitive expeditions to apprehend and punish freedom fighters, at times with British assistance.

The German effort included the first commercial enterprises in the 1850s and 1860s in West Africa, East Africa, the Samoan Islands, and the unexplored north-east quarter of New Guinea with adjacent islands. German traders and merchants began to establish themselves in the African Cameroon delta and the mainland coast across from Zanzibar. At Apia and the settlements Finschhafen, Simpsonhafen and the islands Neu-Pommern and Neu-Mecklenburg, trading companies newly fortified with credit began expansion into coastal landholding. Large African inland acquisitions followed, mostly to the detriment of native inhabitants. All in all, German colonies comprised territory that makes up 22 countries today, mostly in Africa, including Nigeria, Ghana, and Uganda.

As Bismarck was converted to the colonial idea by 1884, he favoured “chartered company” land management rather than establishment of colonial government due to financial considerations. Although temperate zone cultivation flourished, the demise and often failure of tropical low-land enterprises contributed to changing Bismarck’s view. He reluctantly acquiesced to pleas for help to deal with revolts and armed hostilities by often powerful rulers whose lucrative slaving activities seemed at risk. German native military forces initially engaged in dozens of punitive expeditions to apprehend and punish freedom fighters, at times with British assistance.

Bismarck’s successor in 1890, Leo von Caprivi, was willing to maintain the colonial burden of what already existed, but opposed new ventures. Others who followed, especially Bernhard von Bülow as foreign minister and chancellor, sanctioned the acquisition of the Pacific Ocean colonies and provided substantial treasury assistance to existing protectorates to employ administrators, commercial agents, surveyors, local “peacekeepers,” and tax collectors. Kaiser Wilhelm II understood and lamented his nation’s position as colonial followers rather than leaders. In an interview with Cecil Rhodes in March 1899 he stated the alleged dilemma clearly: “Germany has begun her colonial enterprise very late, and was, therefore, at the disadvantage of finding all the desirable places already occupied.”

According to historian William Roger Louis, in the years before the outbreak of the World War, British colonial officers viewed the Germans as deficient in “colonial aptitude,” but “whose colonial administration was nevertheless superior to those of the other European states.” Anglo-German colonial issues in the decade before 1914 were minor, and both the British and German empires took conciliatory attitudes. Once war was declared in late July 1914 Britain and its allies promptly moved against the colonies, the public was informed that German colonies were a threat. The British position that Germany was a uniquely brutal and cruel colonial power originated during the war. By 1916, only in remote jungle regions in East Africa did the German forces hold out.

According to historian William Roger Louis, in the years before the outbreak of the World War, British colonial officers viewed the Germans as deficient in “colonial aptitude,” but “whose colonial administration was nevertheless superior to those of the other European states.” Anglo-German colonial issues in the decade before 1914 were minor, and both the British and German empires took conciliatory attitudes. Once war was declared in late July 1914 Britain and its allies promptly moved against the colonies, the public was informed that German colonies were a threat. The British position that Germany was a uniquely brutal and cruel colonial power originated during the war. By 1916, only in remote jungle regions in East Africa did the German forces hold out.

Exercises:

1. Re-read the text, make up a list of necessary vocabulary and answer the following questions:

1) What is Realpolitik?

2) Who was the first man to successfully unify Germany?

3) What did he do to unify Germany?

4) Did Germany have any colonial ambitions?

5) What is Weltpolitik?

6) What continent was the priority for the German colonial expansion?

7) How was the German colonial leadership considered by the other colonial superpower?

2. Find in the text the following words and word combinations, find a Russian equivalent for them and add them to your working vocabulary:

a proponent; to pit; leniency; to accredit; to play catch-up; nationhood; place in the sun; a scramble; entrepreneurs; coastal landholding.

3. Use the words from the Exercise 2 in your own sentences.

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.

5. Write an essay on the following topic:

"Would it have been better if Germany absorbed Austria-Hungary as they began their unification? Would it have been worse? Why?"

1) What is Realpolitik?

2) Who was the first man to successfully unify Germany?

3) What did he do to unify Germany?

4) Did Germany have any colonial ambitions?

5) What is Weltpolitik?

6) What continent was the priority for the German colonial expansion?

7) How was the German colonial leadership considered by the other colonial superpower?

2. Find in the text the following words and word combinations, find a Russian equivalent for them and add them to your working vocabulary:

a proponent; to pit; leniency; to accredit; to play catch-up; nationhood; place in the sun; a scramble; entrepreneurs; coastal landholding.

3. Use the words from the Exercise 2 in your own sentences.

4. Write your summary of the text, emphasising in it:

a) its subject matter,

b) the facts discussed,

c) the author's point of view on these facts.

5. Write an essay on the following topic:

"Would it have been better if Germany absorbed Austria-Hungary as they began their unification? Would it have been worse? Why?"